On Monday 12 April as the 3rd COVID lockdown started to ease and the majority of outdoor settings, non-essential retail shops, venues and attractions reopened Tracy and I met and socially distanced in Tatton Park, instead of going to the hairdressers or having a drink in a pub.

Our aim was to read the visible scenery, landforms, and vegetation to pick up the clues and sense and interpret the hidden geological landscapes below us we walked through the Park to the Courtyard restaurant and back.

Mid Cheshire is known to be the centre of salt workings for 2000 years or more, continuously from pre Roman times to until now. Centred on the Cheshire Salt Towns ending in ‘wich’ such as Nantwich, Middlewich, and Northwich (which includes the village of Leftwich, now there’s a good address …. London Road, Leftwich, Northwich!)

But there are other towns too that are built on salt, have exploited salt, have been marked by salt’s solubility; Winsford, Sandbach and even Knutsford. The ancient rock salt is in layers up to 300 metres thick. When these are near the surface water seeps down and dissolves the solid salt leaving a void below ground, forming brine and an unstable collapse land surface with sink holes, depressions, linear troughs and valleys. Natural Underground brine streams flow through the collapsed ground reaching the surface as brine springs, first exploited in the Iron Age and then by brine wells, brine pumping and salt mining especially over the last 300 to 400 years. Pumping from the underground brine encouraged the formation and extensive spread of the brine streams and overlying unstable collapse land surface.

Q. So how is this relevant to Tracy and I, as we stroll through Tatton Park?

A. Tatton Park and Tatton Hall are underlain by salt, just below the surface.

Have a look at a geological map https://mapapps.bgs.ac.uk/geologyofbritain/home.html

Q. But if you can’t see the salt on the ground in front of you how do we or the map makers know it’s there?

A. We need to gather some clues.

Which is what Tracy and I did as we walked through Tatton Park from the Knutsford Gate up to the Courtyard Cafe for a cuppa.

Through the gate entrance, keeping to the left, the land stretched roughly level to the north but dropped away to the east. Probably down about 10 to 15 metres to the long wide valley with Tatton Mere. The land then rose again and was level with wooded skyline across to the level land of the runways of Manchester airport.

Now here’s how to find some the geological clues. Ask some questions.

Q. Why is some ground low and some high?

A. It’s rock strength. Weak soft rocks are easily eroded, are worn away by rivers and ice so form low ground.

Q. Is Tatton Mere/Valley formed by river eroded soft rocks?

A. There is very little slope on the valley.

Tatton Mere is artificial, it appears to be dammed at both the northern the southern ends which suggests it wasn’t a former distinct linear valley draining either to the south or the north.

Tracing the Tatton Mere valley south into Knutsford, the low ground runs through the Moor open recreation space (with many of years of drainage problems) south through housing eventually petering out near Toft as the ground rises.

It is not a valley.

Its linear trough with no exit.

Now that suggests to me that the ground has sunk rather than the ground has been eroded and removed by the flowing river water.

Q. Has the ground sunk when the rocks below have been removed by mining? By solution? A. No sign of mining in Tatton Park.

No shafts, no pit mounds, no railway lines.

Q. What rocks are soluble?

A. Limestone. Yes but it’s a fairly tough rock, so resists erosion and forms high ground like the Pennines or pokes up through the grass. There’s no sign of limestone rocks or any others poking up through the grass in Tatton Park – so I conclude the Tatton Mere trough is unlikely to have underlain by collapsed limestone caves.

Q. But what about rock salt?

A. Rock salt is a weak rock that dissolves and leaves sink holes and linear closed ended subsidence troughs. Now that seems to match the Tatton Mere trough.

So off Tracy and I go hunting for more clues, checking the landscape.

We keep walking over the level ground along the eastern margin of the Tatton Park.

Walking north with the Park Road and the Mere on our right.

Then we reach an edge, the level ground then falls away in front of us.

A 5m steep slope, an escarpment parallel to the Mere.

The steep slope stretches NNW toward Tatton Hall.

In fact there’s a series of 2 to 3 scarps with intervening wide steps that go down 10 to 15m and parallel the shoreline of Tatton Mere and Melchett Mere further north.

Stepped scarp slopes are typical of unstable slope. Evidence of ground movement, landslips.

Now if you add water to any ground it reduces its stability, loosens everything up.

The angle of repose is decreased, slope stability decreases, the land becomes unstable and slips and slides downhill.

There’s certainly plenty of soggy wet ground at the base of each scarp slope and between Tatton Mere and Melchett Mere.

Q. But what is the ground made of?

A. If there is solid rock salt here it would soon dissolve in our sweet refreshing British rain so we won’t see any rock salt on the surface.

Q. But rock salt might be not far below ground, is the salt further down?

Q. Can the rain and surface water and ground water reach it?

Q. Is the groundwater dissolving away the rock salt?

A. We need some help.

Ah Ha!

The moles are here to help us, they have freshly turned up soil in mole hills.

A pinch of soil rubbed between the fingers leaves no dirty clayey marks and feels like caster sugar.

Conclusion it’s a sandy soil. Sandy soil has a high porosity and high permeability.

That is soil that holds a lot of water and lets a lot of water flow through it.

So a sandy soil will defiantly be a conduit for water to reach solid salt beneath.

Okey Dokey lets look for some more circumstantial evidence to support my developing theory that Tatton Park is underlain by rock salt that is slowly dissolving.

By now, Tracy and I are in real need for a cuppa, so we keep heading NNW alongside Melchett Mere.

And why not Google ‘Tatton Park Melchett Mere’ as we go. It comes up with Lord Melchett.

Q.Is there a link to the Lord Melchett of Blackadder fame?

A. No.

‘Lord Melchett… was… Sir Alfred Moritz Mond … who, together with John Tomlinson Brunner, set up the great chemical company which developed in 1881 into the public joint-stock company Brunner, Mond & Co.’ https://liberalhistory.org.uk/history/mond-sir-alfred-lord-melchett/

Now there’s two names that are very familiar in the Cheshire Salt Towns.

Brunner, Mond & Co. was the precursor to ICI.

And Goggle gave us the link to Tatton Park, Melchett Mere and Salt

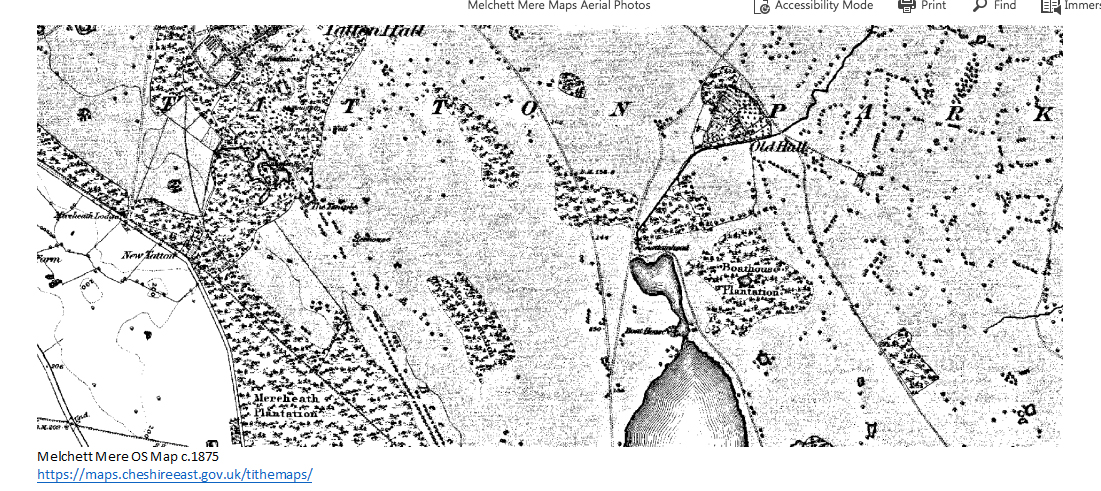

‘It was probably C19th and early C20th pumping of wild brine by salt companies based at Northwich which dissolved the rock salt under and to the north of Tatton Mere, causing the sudden collapse in 1922 which resulted in the creation of Melchett Mere, named by Lord Egerton after the then chairman of the extractive company he believed to have been responsible. This relatively new expanse of surface water lies at the lowest point of a solution valley, the sides of which are characterised by subsidence cracks.’ https://heritagerecords.nationaltrust.org.uk/HBSMR/MonRecord.aspx?uid=MNA113900

And to put the cherry (or yellow spot) on the cake, as Tracy and I walked around Melchett Mere, we kept coming across small 15cm yellow square plastic markers in the ground. Locations that are surveyed regularly to check the height of the ground – a sure sign that the Earth is on the move and being monitored in Tatton Park.

Ground marker – Tatton Park

Feeling very delighted to have had a good reading of the landscape and now beginning to understand Tatton Park’s visible and hidden landscapes, we walked on to our tea stop.

Admiring, as we passed the undulating salt subsidence depressions in the enclosed deer pasture between the front of Tatton Hall and Home Farm. Showing that the underground salt and brine stream with its accompanying surface subsidence is running NNW towards The Mere at Mere, where the shallow buried salt/brine stream then veers southwards through Meremoss Wood, Tableymoss Wood heading towards Tabley Hall and Tabley Mere.

Rested and refreshed after our cuppas, we then enthused over the lumps and bumps of the Park Road along the northeast side of Melchett Mere, where subsidence cracks and scarps cross the road. Classic examples of active ground subsidence.

So I rest my case, my reading of Tatton’s Hidden Landscape is a 240million year old salt lake legacy.

Under the gently rolling rural landscape and small towns of mid Cheshire, lies vast resources of halite (rock salt) of Triassic age when Cheshire was an arid, desert basin with salt lakes, just north of the equator. The salt lakes frequently evaporated leaving behind crystals of solid salt, sometimes covered with mud blown in by the wind. In rainier times thicker layers of mud formed. Over time a great pile of mudstone and halite beds built up to about 1500 metres thick.

And Tatton’s landscape of very long ago is still shaping Tatton’s landscape of today, and will continue to do so in the future.

Ros Todhunter 10 May 2021

Leave A Comment